Stern Verve: Joseph Zito at Lennon, Weinberg.

August 19, 2015 · by Jonathan Stevenson

Installation view at Lennon, Weinberg

Installation view at Lennon, Weinberg

The artist’s weight in ominous lead slabs, a combat helmet spilling with rose petals – in another artist’s hands these conceptual pieces would probably seem trite or overbearing. But Joseph Zito’s unerringly fine calibrations of irony combined with his formidable technical range and astutely Gober-esque deployment of different materials – all on full display in installations cagily concatenated for a thirty-year retrospective at Lennon Weinberg in Chelsea – enables him to steamroller cliché and proceed directly to cool-eyed poignancy.

My Weight in Lead, 1992

The practically unliftable slabs of My Weight in Lead (1992) are strung together like rungs in a rope ladder, amplifying their uselessness and perhaps anticipating a weary, post-Serra point of view. Indeed, a key to Zito’s efficacy is his controlled infusion of what he calls “primal emotions” into objects he admits are outwardly Minimalist/Conceptual. Zito uses size and especially negative space to lend nuance to his angst. Adrift (2013), a tiny bronze dory, created in an "edition of one," fixed in a southeasterly slant on an expanse of white wall, embodies not just objecthood but solitude and its perpetual nature. In Stand Still God Damn It (2012), an hourglass with unmoving red sands imparts the creeping agony of time’s passage.

My Weight in Lead, 1992

The practically unliftable slabs of My Weight in Lead (1992) are strung together like rungs in a rope ladder, amplifying their uselessness and perhaps anticipating a weary, post-Serra point of view. Indeed, a key to Zito’s efficacy is his controlled infusion of what he calls “primal emotions” into objects he admits are outwardly Minimalist/Conceptual. Zito uses size and especially negative space to lend nuance to his angst. Adrift (2013), a tiny bronze dory, created in an "edition of one," fixed in a southeasterly slant on an expanse of white wall, embodies not just objecthood but solitude and its perpetual nature. In Stand Still God Damn It (2012), an hourglass with unmoving red sands imparts the creeping agony of time’s passage.

Stand Still Goddamn It, 2012

Stand Still Goddamn It, 2012

A virtuously restless artist, Zito also drills into more particular political and social issues such as war and race. The helmet of Untitled (helmet) (2005) is not a genuine soldier’s cover but rather a translucent facsimile made of cast glass laid on a truncated steel pedestal: sprinkled with flowers, it’s a sardonic comment that a helmet’s protection is substantially illusory, and that military death, while dutifully beautified and memorialized, remains mainly unseen, at foot level. The seven metal points rising aggressively from the floor nearby, resembling a missile array, are notably higher, as are the infant body bags fading heavenward in Ascension (2005). Three painted copper cookie jars shaped like black housemaids hanging on a tether from a lawn jockey’s hand in Mammy (1996) sound a sweet note when struck, signifying the disguised corrosiveness of whites’ subjugation of blacks, and prefiguring work like Nick Cave’s.

Adrift, 2013

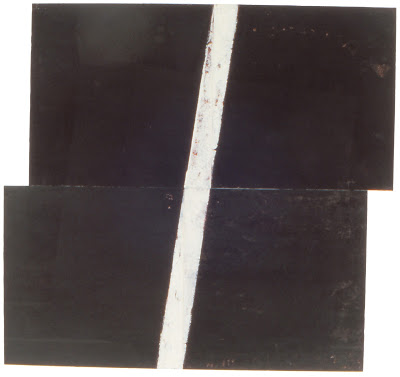

Zito’s work on paper is comparably penetrating and resourceful. Gunpowder drawings trenchantly capture the morbid transience of war. In the

magisterially economical oil-on-

paper For Max (1988), two staggered, imperfect black rectangles intersected by a bold white

line suggest at once the temporary utility and the ultimate futility of manmade order.

Adrift, 2013

Zito’s work on paper is comparably penetrating and resourceful. Gunpowder drawings trenchantly capture the morbid transience of war. In the

magisterially economical oil-on-

paper For Max (1988), two staggered, imperfect black rectangles intersected by a bold white

line suggest at once the temporary utility and the ultimate futility of manmade order.

For Max, 1988

For Max, 1988

Perhaps the crowning set of pieces in the retrospective consists three spare watercolors – one of a spectrally white chair tilted on its side and floating near the top edge of the frame, another of a toppled ashen black chair situated near the bottom edge, and a third of a blood-red chair similarly positioned, all titled The Red Chair (2015)– hung near an identically named hydrostone cast of the studio chair Zito used for decades. He obliterated the original chair in the very act of making the sculpture. If that is the chair’s grave, the images in the paintings represent its physical absence, its ghostly presence, and possibly its lasting inspiration. These pieces may be Zito’s way of saying that artists must get up and move on, while never forgetting. As he does himself, with stern resolve and passionate verve.

The Red Chair, 2015

The Red Chair, 2015